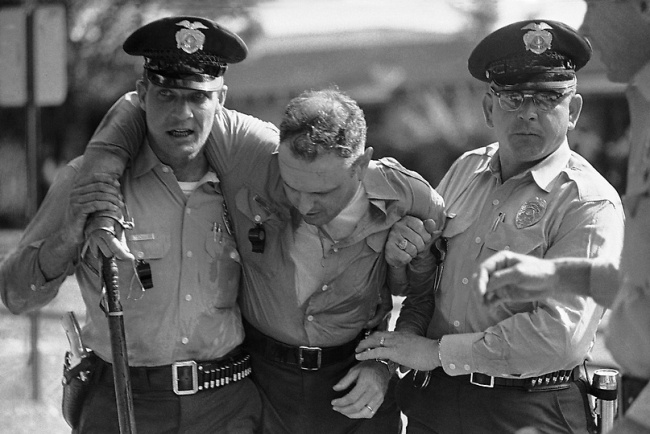

Above: Birmingham police injured by rocks thrown by protesters, May 7, 1963 (AP Photo)

“My dream has become a nightmare,” Martin Luther King said in 1967, as a government he’d hoped could end racism and poverty instead escalated towards genocide in Vietnam. Protesters in America would need to flirt with guerilla warfare before that particular nightmare ended [1]; but what gave Dr. King the courage to dream in the first place? Was it simply The Beloved Community, The Power of Nonviolence, and the Openness of American Liberalism like our schoolteachers—and pacifist NGO trainers—told us? Or was all of this mixed with stronger medicine?

This week the left goes through its annual ritual of discussing the “forgotten radicalism” of Dr. King; but it’s time we engaged with the deeper radicalism of the overall struggle which made the man. One of these radical aspects was the movement’s willingness (from an early stage) to employ diversity of tactics , including self-defense and disruptive rebellion, without which it would have been strangled in its cradle by the twin threats of right-wing terror and liberal complacency.

The nonviolent civil rights movement remains the historical bedrock on which most activists’ credo is grounded. But on closer historical scrutiny, the bedrock turns out to be sand. There’s great emotional incentive to cling to the myths, of course; the perceived legal hazards and ethical complexities of using force are daunting, even for self-proclaimed revolutionaries. No one, however, designs effective strategy on the basis of bad history. Nonviolent witness “makes for a good narrative, but it is not a reliable recipe for social transformation,” writes historian Timothy Tyson. “We cherish the conventional story of Dr. King and nonviolence, in fact, precisely because that narrative demands so little of us…This conventional narrative is soothing, moving, and politically acceptable, and has only the disadvantage of bearing no resemblance to what actually happened.” [2]

21 Quotations on a Militant Era

“[Dr. King’s philosophy] didn’t accomplish what it should have because the white establishment would not accept his philosophy of nonviolence and respond to it positively”.

– Rosa Parks, quoted in The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks by Jeanne Theoharis, p.196

“We cannot take these people who do us injustice to court and it becomes necessary to punish them ourselves…If we feel that injustice is done, we must right then and there on the spot be prepared to inflict punishment on these people. I feel this is the only way of survival…We will meet violence with violence.”

– Robert F. Williams, president of Monroe, North Carolina chapter of the NAACP, quoted on the May 6, 1959 front page of The New York Times

“Any effort, from here on out, to keep the Negro in his ‘place’ can have only have the most extreme and unlucky repercussions…The Negroes who rioted at the UN are but a very small echo of the black discontent now abroad in the world.”

– James Baldwin (commenting on a militant protest organized by Maya Angelou and Leroi Jones against the assassination of Patrice Lumumba), The New York Times Magazine, March 12, 1961, “A Negro Assays the Negro Mood”

“Albany [Georgia], it seems to me, was the first dramatic evidence of a phenomenon which now has been seen often enough to be believed: that there is a part of the South impermeable by the ordinary activities of nonviolent direct action…And for this South, special tactics are required… I am now convinced that the stone wall which blocks expectant Negroes in every town and village of the hard-core South, a wall stained with the blood of children, as well as others, and with an infinite capacity to absorb the blood of more victims — will have to be crumbled by hammer blows.”

– Howard Zinn, “The Limits of Nonviolence,” 1964 [3]

“[Reverend Wyatt Tee] Walker asserted that everything must build. If they showed strength, then outside support would grow more than proportionately. Once started, however, they could not fall back without suffering letdown and depression, which in Birmingham risked a fatal outbreak of Negro violence.”

– Taylor Branch, Parting the Waters: American in the King Years 1955-1963, p. 690

“[On April 7,] Bull Connor displayed one of the weapons that Walker had been hoping for: a squad of snarling police dogs. A large crowd gathered as police arrested the two dozen marchers. One black bystander lunged at a dog with a large knife. As the New York Times described it, ‘The dog immediately attacked and there was a rush of other Negroes toward the spot where the dog had pinned the man to the ground. Policemen with two more dogs and other policemen who were congregated in the area quickly rushed against the crowd, swinging clubs.’ … the chance gathering of that late-afternoon crowd, and one man’s unrestrainable anger toward the police dogs, had suddenly given the movement the national coverage King and Walker had been seeking”

– David J. Garrow, Bearing the Cross: Martin Luther King Jr and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, p. 239

“…Wyatt Walker served as overall field general, coordinating tactical moves…One example, Walker said later, was dispatching ‘eight or ten guys to different quarters of the town to turn in false alarms.’… Walker’s tactics were aimed at depleting Connor’s forces…in subsequent years Walker made no apologies for employing tactics he felt would be effective for revealing to the entire nation the racist brutality of Connor and the system he represented. ‘I had to do what had to be done,’ Walker explained, ‘At times I would accommodate or alter my morality for the sake of getting a job done…I did it consciously. I felt I had no choice. I wasn’t dealing with a moral situation when I dealt with Bull Connor.’”

– David Garrow, Bearing the Cross, p. 248

“Black onlookers gathered along the fringes of Kelly Ingram Park, and some hurled verbal taunts at the white officers. Connor was on the scene and ordered six police dogs deployed to force the crowd back. The sight of the snarling dogs further roused the hostility of the onlookers, and rocks and bottles began to sail out of the crowd toward the police and firemen. Then Connor ordered the dogs into action, and instructed the powerful hoses be used to drive the demonstrators and bystanders from the park…”

– David Garrow, Bearing the Cross, p. 249

“Birmingham would’ve been lost if Bull had let us go down to the City Hall and pray; if he had let us do that and stepped aside…there would be no movement, no publicity.”

– Rev. Wyatt Tee Walker, quoted in David Garrow, Bearing the Cross, p. 250

“The Reverend Walker…he said that the Negroes, when dark comes tonight, they’re going to start going after the policemen – headhunting – trying to shoot to kill policemen. He says it’s completely out of hand…The sheriff’s office said that if they had the same kind of situation as last night again, they wouldn’t be able to control them….you could trigger off a good deal of violence around the country now, with Negroes saying they’ve been abused for all these years and they’re going to follow the ideas of the Black Muslims now…If they feel on the other hand that the federal government is their friend, that it’s intervening for them, that it’s going to work for them, then it will head some of that off. I think that’s the strongest argument for doing something…”

– Robert F. Kennedy in meeting with President Kennedy, May 12, 1963 [ JFK Presidential Library, “Meetings:Tape 86” ]

“President Kennedy feared that black Southerners might become ‘uncontrollable’ if reforms were not negotiated. It was one of the enduring ironies of the civil rights movement that the threat of violence was so critical to the success of nonviolence.”

– Timothy B. Tyson, “Civil Rights Movement” in The Oxford Companion to African-American Literature, p. 149

“In many cities, Birmingham solidarity rallies became shows of black defiance… In Chicago, nearly three thousand black teenagers pelted the police with bricks and bottles to express their outrage at police brutality in Birmingham and in their own city. A week later, a group of blacks beat Chicago mayor Richard J. Daley’s nephew, shouting ‘This is for Birmingham!’ as they pummeled him…Hardly any city seemed immune to what observers deemed ‘near riots’”

– Thomas Sugrue, Sweet Land of Liberty: The Forgotten Struggle for Civil Rights in the North, p. 291-303

“Because Cambridge [Maryland] is so physically close to Washington, we asked ourselves, ‘First can we create enough chaos with our movement to force the Kennedy’s attention to be focused on this area? And then, what would they be likely to do?”

– Gloria Richardson ( leader of the Cambridge, Maryland chapter of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee 1961-1964, official honoree of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, 1963 ), quoted in Hands on the Freedom Plow: Voices of Women in SNCC, p. 281

“The state police were going from house to house, looking for guns in the black community…In the process of conducting this search, they sicced the dogs on a white newsman and a local blackman…That night, at the end of one long block, twelve black men came and garroted the dogs, killing them. The state captain called me in the next morning to complain…I told him ‘Yes, if you continue to send your men down here in middle of the night looking for guns and hurting people, your men might get killed too.’”

– Gloria Richardson, quoted in Hands on the Freedom Plow, p. 292

“I and the others in the NAACP have armed. We will shoot first and answer questions later. We are not going to die like Medgar Evers.”

– Dr. Robert Hayling, president of the St. Augustine Florida NAACP, June 18, 1963, quoted in Taylor Branch, Pillar of Fire: America in the King Years 1963-1965, p. 111

“In 1961 and 1962, freedom riders and other activists were the targets of violence by whites in one place after another…By 1963 however, white aggression began to precipitate a black response, usually taking the form of mass rioting, as in Birmingham, Savannah, and Charleston. On March 24, 1964, blacks in Jacksonville [Florida] attacked the police, assaulted other whites, looted and damaged property, and introduced the use of Molotov cocktails – all this in the wake of court convictions of black sit-in participants.”

– Francis Fox Piven and Richard Cloward, Regulating the Poor, p. 238

“[If the Civil Rights Act is defeated] our nation is in for a dark night of social disruption.”

– Martin Luther King Jr, press conference at Capitol Hill, March 26, 1964

“It was stones yesterday, Molotov cocktails today; it will be hand grenades tomorrow and whatever else is necessary the next day. The seriousness of this situation must be faced up to. If you take the warning, perhaps you can still save yourself. If you ignore it, or ridicule it, then death is already at your doorstep.”

– Malcolm X, April 8, 1964, quoted in Malcolm X Speaks, p. 48

“Gloria and her followers have been preparing for war with police, National Guard, and federal troops, if necessary, in an all-out battle for their rights…Negro demonstrators shot nearly a dozen guardsmen in separate incidents, beat scores more with rocks and stones and broke one Negro guardsman’s arm when he tried to throw a gas grenade…”

– Ebony, “Gloria Richardson: Lady General of Civil Rights,” July 1964, p. 23

“So tonight I urge every public official, every religious leader, every business and professional man, every workingman, every housewife—I urge every American—to join in this effort to bring justice and hope to all our people—and to bring peace to our land.”

– Lyndon B. Johnson, remarks on signing the Civil Rights Act, July 2, 1964

“Our people have made the mistake of confusing the methods with the objectives. As long as we agree on objectives, we should never fall out with each other just because we believe in different methods or tactics or strategy to reach a common goal.”

– Malcolm X, “The Black Revolution”, April 8, 1964

________________________________________________________________

1. In their book Black Against Empire: The History and Politics of the Black Panther Party (University of California Press, 2013), historians Joshua Bloom and Waldo Martin demonstrate that the specter of domestic guerilla warfare raised by the Panthers and other militants was a factor in pressuring Richard Nixon to bring the war to a close.

2. Timothy Tyson, Blood Done Sign My Name (Broadway Books, 2005) p. 317-318

3. In “The Limits of Nonviolence,” Zinn stated that the federal government was his preferred agent of force against segregationists. By 1965, however, he accepted and justified the movement’s use of violence: “The members of SNCC- and indeed the whole civil rights movement – have faced in action that dilemma which confounds man in society: that he cannot always have both peace and justice. To insist on perfect tranquility with an absolute rejection of violence may mean surrendering the right to change an unjust social order. On the other hand, to seek justice at any cost may result in bloodshed so great that its evil overshadows everything else and splatters the goal beyond recognition. The problem is to weigh carefully the alternatives, so as to achieve the maximum of social progress with a minimum of pain. Society has been guilty of much quick and careless weighing in the past…on the other hand, it has permitted the most monstrous injustices which it might have eliminated with a bit of trouble.” Howard Zinn, SNCC: The New Abolitionists (South End Press 2002 edition) p. 223